TIMELINE

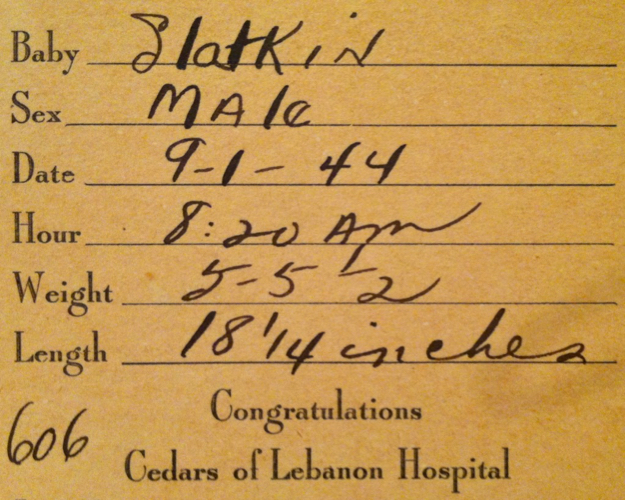

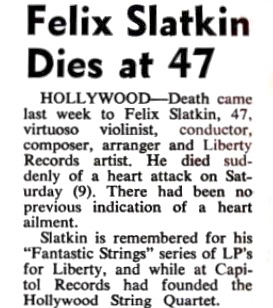

His father, Felix Slatkin, was concertmaster of the 20th Century Fox Orchestra, while his mother, Eleanor Aller, was first cellist for Warner Brothers. Together they formed one half of the Hollywood String Quartet, an ensemble regarded for its exceptional recordings.

“My father hardly ever practiced. He could just pick up a violin after three or four weeks off and produce an extraordinary Tchaikovsky concerto. My mother always resented that he didn’t have to work so hard; she had to practice like a dog, about four or five hours a day.”

—Leonard Slatkin

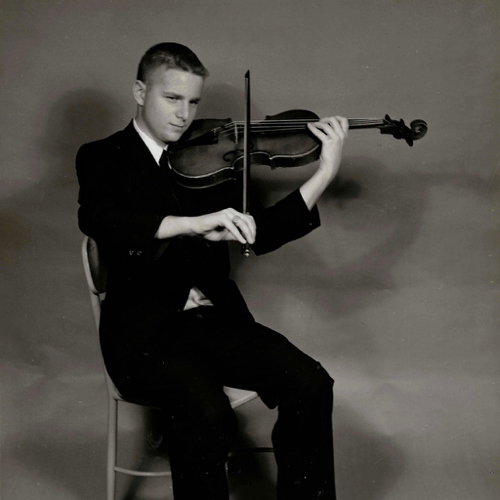

“I began piano lessons with [my grandfather] Gregory after realizing that I would not be nearly as good a violinist as my father. When it appeared that I had some aptitude for this instrument, Gregory sent me to study with his son, my uncle Victor.”

—Leonard Slatkin, Conducting Business

“Along with piano, I took up the viola. It was the string instrument that no one else in the family played. It was also the instrument that nobody at either my junior high or high school attempted to master. There exists a truly appalling recording from one of our spring concerts, where the ‘Unfinished’ Symphony was on the program. At one point, after a glorious buildup, the orchestra stops and the viola part is exposed, playing a little rhythmic figure. I was the lone violist. If anyone ever finds that recording, it might be used against me.”

—Leonard Slatkin, Conducting Business

Leonard led the viola section of the California Junior Symphony, aka the Meremblum Orchestra. He is pictured here as principal viola with his younger brother, Fred, principal cello. The conductor is Mehli Mehta, father of Zubin Mehta.

Leonard conducted the Aspen Festival Orchestra in Barber’s Adagio for Strings. When he asked Susskind if he could return the next summer, his mentor smiled and said, “You had better.”

“Never forget that you have a responsibility to the composer, musicians, and audience. The responsibility to yourself comes last.”

—Walter Susskind

“Five days a week, we would meet in his studio, always adhering to the same regimen, beginning with solfège exercises. I think I drove him nuts with my inability to master more than a few syllables, quickly invoking whatever sounds I could think of. With perfect pitch, I could sing the right notes, just with the wrong words.”

—Leonard Slatkin, Conducting Business

“Slatkeen, what is this fa-la-la?”

—Jean Morel, at every lesson

Leonard was invited to be assistant conductor of the Youth Symphony Orchestra of New York under the direction of David Epstein, leading them in a performance of William Schuman’s New England Triptych.

“With that first step through the doors and onto the stage, I felt overwhelmed by the sense that the auditorium had at least quadrupled in size.”

—Leonard Slatkin, Conducting Business

After conducting a performance of Hindemith’s Symphonic Metamorphosis of Themes by Carl Maria von Weber at the Aspen Festival, Leonard was introduced to St. Louis Symphony Executive Director Peter Pastreich, who offered him the job on the spot. Leonard’s conducting teacher, Walter Susskind, had been named music director in St. Louis.

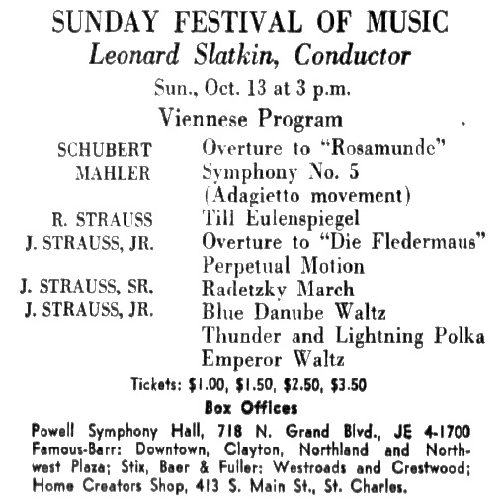

Slatkin’s program for his first performance with the orchestra featured all-Viennese repertoire with works by Schubert, Mahler, Richard Strauss, and Johann Strauss Jr. and Sr.

The top ticket price was $3.50.

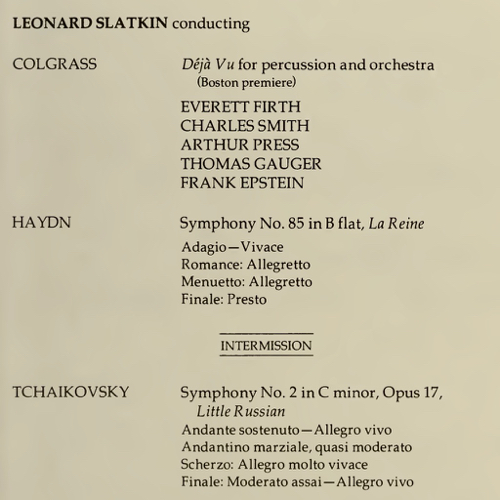

The program featured Schuman’s Credendum: An Article of Faith, Mozart’s Piano Concerto No. 21 with soloist Géza Anda, and Rachmaninoff’s Second Symphony.

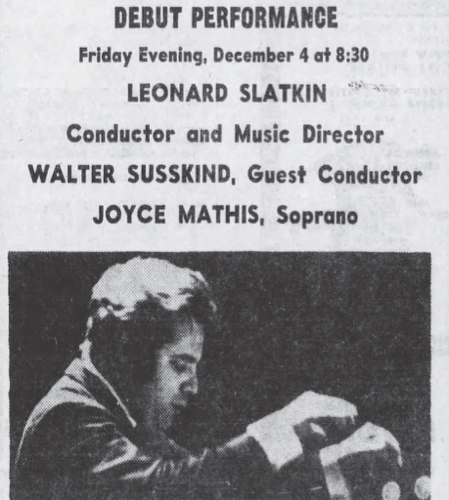

Leonard has cited the founding of the St. Louis Symphony Youth Orchestra as the initiative he is most proud of in his career. The opening program included a transcription of the Bach Passacaglia and Fugue in C minor; vocal selections by Mozart, Puccini, and Gershwin with soprano Joyce Mathis; and Milhaud’s Suite provençale.

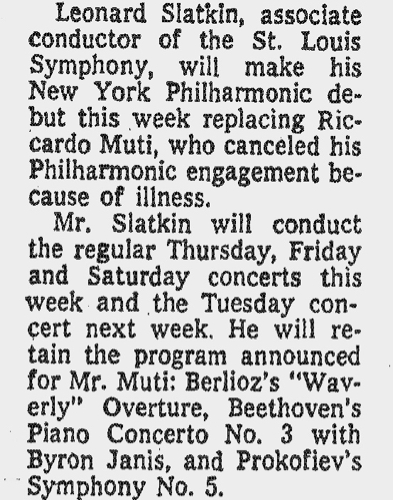

Slatkin received a phone call on a Sunday afternoon from New York Philharmonic Executive Director Nick Webster, who asked him to fill in to replace Riccardo Muti. The program comprised Berlioz’s Waverly Overture, Beethoven’s Third Piano Concerto with soloist Byron Janis, and Prokofiev’s Fifth Symphony. “That night,” Leonard recalled, “I saw the Berlioz for the first time. Fortunately, I owned a copy, but I had never opened its covers.”

Nevertheless, audiences were enthusiastic and reviews were mostly favorable. Donal Henahan of the New York Times said that he “conducted Mr. Muti’s original program with professional aplomb and made a considerable splash at times with Prokofiev’s Symphony No. 5.” The New York Post headline was “Philharmonic is saved by Slatkin, a Supersub.” Leonard was immediately re-engaged to conduct the orchestra.

The opening weekend was an all-Prokofiev program: Summer Day, First Violin Concerto with Stuart Canin, and Symphony No. 5. The following week featured an all-Brahms concert: Tragic Overture, Serenade No. 2, and the Second Symphony.

Slatkin was the first to hold the title of principal guest conductor, commencing with the 1974-75 season. He started an eclectic Rug Concert summer series that included electronic and experimental music on the first half of the program. The audience sat on pillows on the floor while listening to such pieces as Ligeti’s Poème symphonique for 100 metronomes.

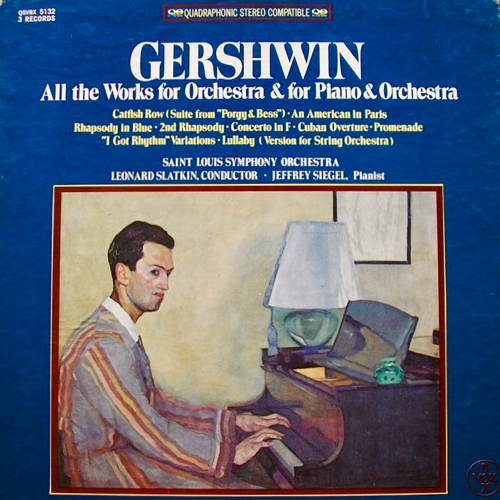

When the St. Louis Symphony began recording for Vox, Walter Susskind generously allowed Leonard to conduct the first albums—the complete works for orchestra by George Gershwin with pianist Jeffrey Siegel. The recordings were released as a three-record set.

“Slatkin’s performances come as a great joy. The sounds is lean and colorful. … The rhythm is firm, but the surfaces swing and bend insinuatingly and delightfully.”

—Michael Steinberg, Boston Globe

Leading the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, Slatkin conducted an English program with music by Walton, Delius, and Vaughan-Williams. He was substituting—on two weeks’ notice—for Sir Adrian Boult.

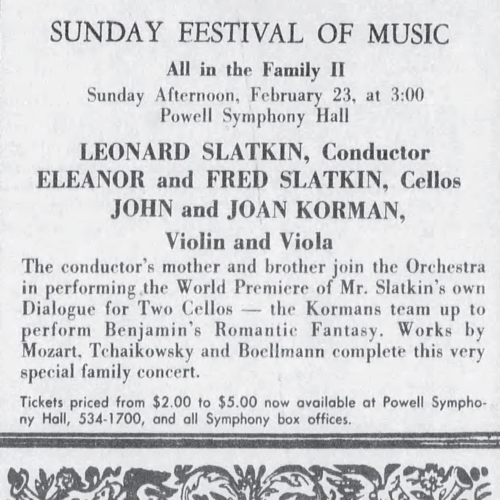

His mother, Eleanor Aller, and his brother, Fred Zlotkin, were soloists on this special program entitled “All in the Family II.” In addition to the piece composed by Leonard, Eleanor performed Boellmann’s Symphonic Variations, and Fred played Tchaikovsky’s Rococo Variations.

“[Slatkin’s ‘Dialogue for Two Cellos’] uses a large orchestra, but sparingly, with a wide palette of color. The style is neoromantic, the form episodic, the idiom easy to assimilate. It works beautifully as a vehicle for two cellists.”

—Frank Peters, St. Louis Post-Dispatch

During the two-year appointment, Slatkin learned how to be a music director—working with four executive directors over two seasons, wading through the audition process, and playing the role of decision-maker for the first time.

“I made a lot of mistakes, but each one was a learning experience. Indeed, running an orchestra was completely different than merely conducting.”

—Leonard Slatkin, Conducting Business

During the course of one week in the spring of 1978, Slatkin was offered music directorships in Cincinnati, Minneapolis, and St. Louis. John Edwards, general manger of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra and a mentor to Leonard, steered him in the direction of St. Louis.

Edwards advised: “Now you know that you are equipped to run a full-time major symphony. What you need is the best management team behind you.”

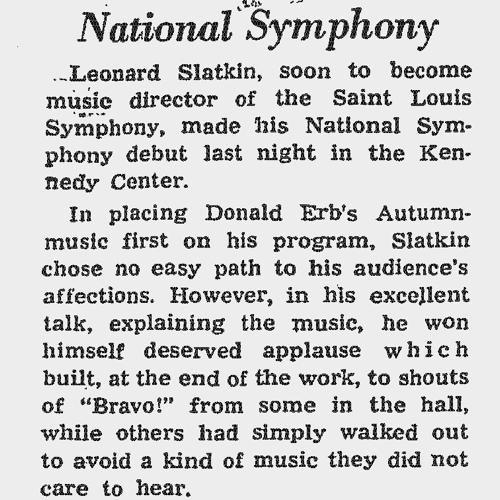

Slatkin opened the concert with Donald Erb’s Autumnmusic, continuing with his strategy to include at least one work by an American composer on the program. He also led the orchestra in the Paganini Violin Concerto No. 2. with soloist Ruggiero Ricci, followed by Sibelius’s First Symphony on the second half.

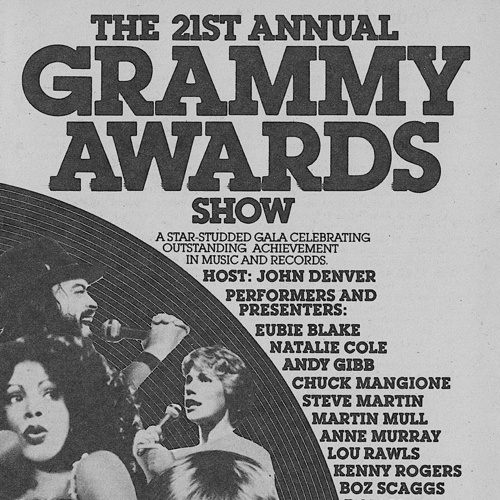

Slatkin was nominated for his recordings with the St. Louis Symphony of Rachmaninoff’s Symphony No. 1 in the Best Classical Orchestral Performance category and Prokofiev’s Alexander Nevsky in the Best Choral Performance category. The winners were Herbert von Karajan for his set of the Beethoven symphonies and George Solti for Beethoven’s Missa Solemnis.

The production was directed by Lou Galterio and starred sopranos Erie Mills as Zerbinetta, Faith Esham as the Composer, and Pamela Myers as Ariadne.

“Awareness of the music was a key element here. Nowhere did Galterio’s direction betray the music or mock it with irrelevant stage business; nowhere did Slatkin fail to support the action with accurate and expressive readings from the pit. It was an Ariadne that one could hear and see with the same enjoyment.”

—Frank Peters, St. Louis Post-Dispatch

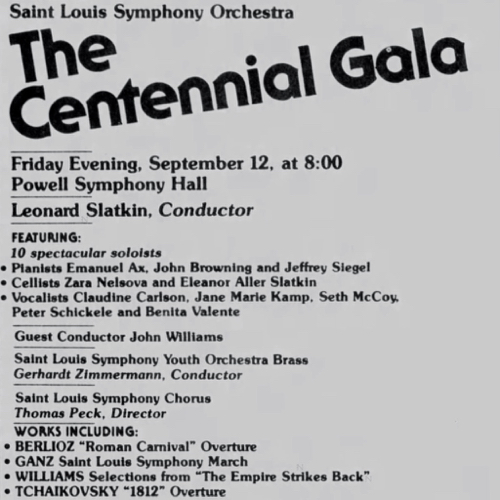

Upon settlement of a six-week strike that delayed the centennial celebrations, the orchestra opened its 100th season with an all-Dvořák program. The concert, which was Leonard Slatkin’s first appearance as music director, featured soloist Mstislav Rostropovich playing the Dvořák cello concerto and a performance of the Ninth Symphony, “From the New World.”

“The symphony [Tchaikovsky’s ‘Little Russian’], like most of the concert, was a testimony to Slatkin’s directness of impulse, skill and musical culture; the Symphony Hall podium is not a place one expects to encounter the best young American conductors, and it was good to find him there. The audience thought so too.”

—Richard Dyer, Boston Globe

In celebration of Isaac Stern’s 60th birthday, Leonard joined conductors Kondrashin, Krivine, Maazel, Marriner, and Ozawa for a series of concerts in and around Paris. He conducted two programs featuring Stern as soloist. The first was with the Orchestre National de France at the Théatre des Champs-Élysées. They performed Verdi’s Sicilian Vespers Overture, the Brahms Double Concerto (with violinist Stern and cellist Hervé Derrien), and the Bartok Violin Concerto No. 2 (with Stern).

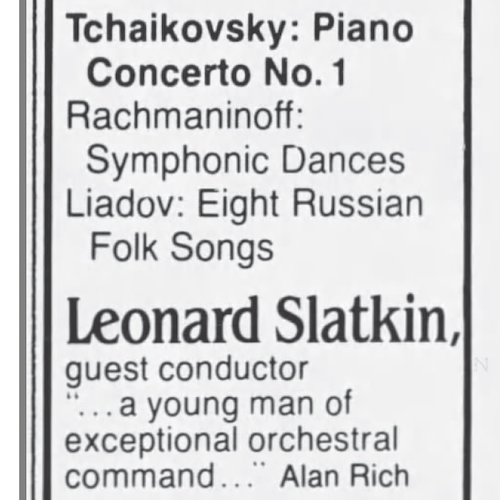

Slatkin conducted the orchestras in Boston, Chicago, and Los Angeles in January 1980; Cleveland in February 1980; New York in June 1980; and Philadelphia in July 1980.

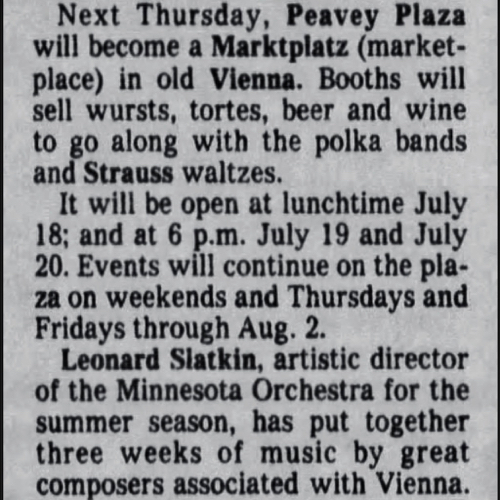

Initially, the festival ran for three weeks, but it was later expanded to four. Concerts ranged from traditional waltzes and polkas to programs featuring new music.

“This was a high point in my career. The orchestra members threw themselves into the most demanding schedule possible and created something that has become a hallmark for the city. After founding the festival, I stayed with it for ten years, loving every moment.”

—Leonard Slatkin

The concert included appearances by composer John Williams and pianists Emanuel Ax, John Browning, and Jeffrey Siegel, among other special guests.

“The highlight was the Aria from Bachianas brasileiras with soprano Benita Valente and my mother as first cellist.”

—Leonard Slatkin

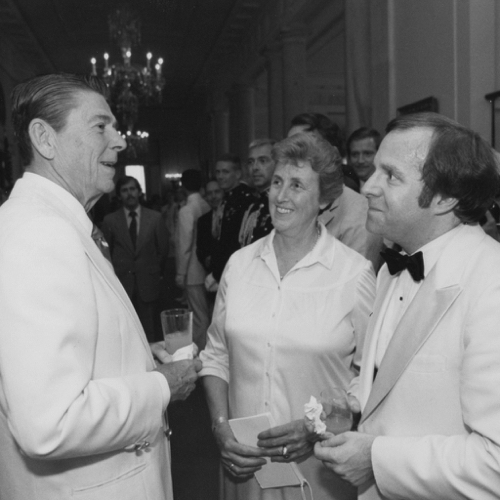

After the concert, President Reagan made remarks. Wearing a white jacket and blue slacks, he turned to the orchestra and said, “The only thing that I have in common with them is that I have a white coat, too.”

“As it turned out, the piece was a hoax. But everyone fell for it, including me, and it even got a favorable review from the New York Times. In the photo, I am discussing the impending cuts to the NEA budget with President Reagan.”

—Leonard Slatkin

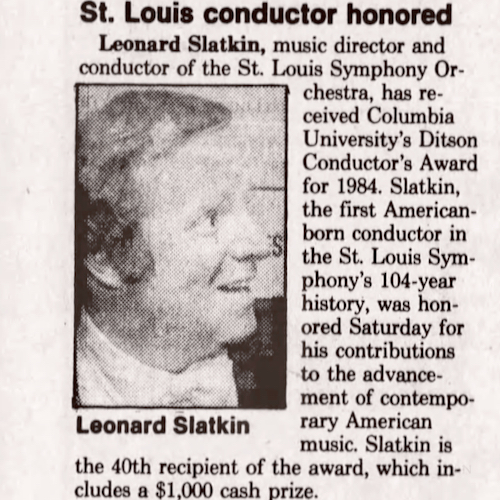

Columbia University bestowed the honor upon him for his contributions to the advancement of contemporary American music. University President Michael I. Sovern acknowledged that throughout his career, Slatkin “has consistently performed music in a wide diversity of styles by American composers.”

Conducted a new production of Massenet’s Werther for Stuttgart Opera. It was the first time the opera had been presented in Stuttgart.

Concerning his interest in conducting opera, Slatkin told the Minneapolis Star and Tribune: “You’ll see me popping up in the pit from time to time. I’m going to be doing things at big houses … but just one [opera] a year. It’s a new interest, and I’m quite fascinated by it.”

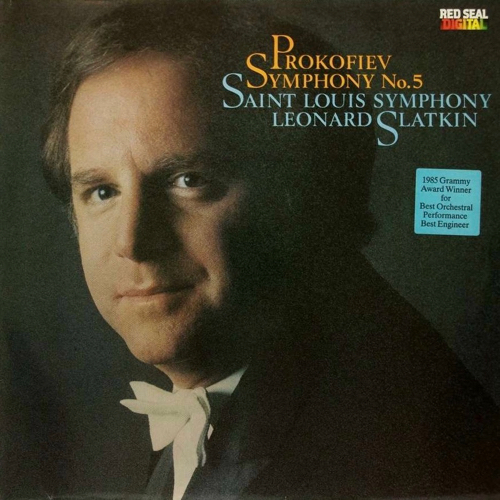

Slatkin won his first GRAMMY for the St. Louis Symphony Orchestra’s 1984 recording on the RCA label of Prokofiev’s Symphony No. 5 at the 27th Annual Grammy Awards. “What this does is to confirm that at least in the United States, the reputation of the orchestra and the quality that it produces is, indeed, being recognized,” Slatkin remarked in an interview with the St. Louis Post-Dispatch.

“I was in Glasgow when the phone rang at 3:00 in the morning,” Slatkin recalled. “Until then, I actually had forgotten that the ceremony was taking place. This was a proud moment for everyone at the SLSO.”

Slatkin was recognized for his outstanding contributions to cultural relations based on his role as founder and artistic director of the Minnesota Orchestra’s Sommerfest. The Austrian Ambassador to the United States, Thomas Klestil, presented him with the honor in Minneapolis on July 16, 1986, acknowledging the festival for promoting the friendship between Austria and the United States.

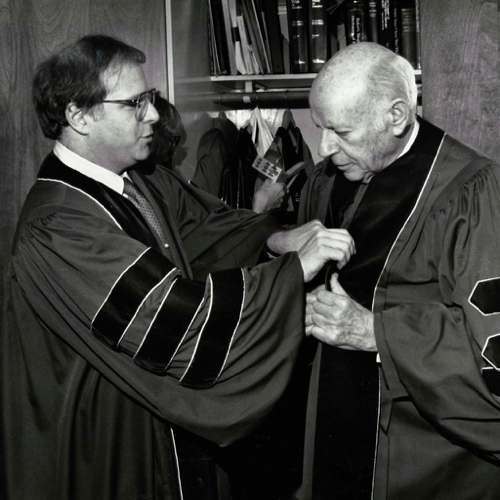

Slatkin received the honorary degree of Doctor of Music in recognition of extraordinary achievement.

“The true honor was to have William Schuman present me with the doctorate. I would return the favor several years later by introducing him for his Kennedy Center Honor.”

—Leonard Slatkin

Slatkin was selected in the second set of ten inductees in a cohort that included General Ulysses S. Grant, authors William S. Burroughs and Kate Chopin, poet Howard Nemerov, actress Betty Grable, trumpeter Miles Davis, and gospel singer Willie Mae Ford Smith. Located in the University City Loop area, the Walk of Fame consists of bronze stars embedded in the sidewalk to honor past and present St. Louisans who have contributed to the country’s cultural heritage.

Leonard Slatkin’s star is located at 6318 Delmar Boulevard.

Slatkin was appointed the first director of the festival, overseeing the orchestra at its summer home in Cuyahoga Falls. The series had a distinctly American flavor, featuring staples by Gershwin, Bernstein, and Copland in addition to lesser-known works by composers Donald Erb and Mark Phillips.

“For nine summers, I had the privilege of leading the prestigious Cleveland Orchestra in its annual set of concerts in an acoustical marvel,” Slatkin recalled. “We had some great evenings of music-making, and I was grateful for this opportunity.”

Slatkin conducted Puccini’s La Fanciulla del West, directed by Giancarlo del Monaco. Barbara Daniels, Placido Domingo, and Sherrill Milnes starred in the production, which was later broadcast on PBS as part of the “Great Performances” series.

“Leonard Slatkin was triumphant—he led the work with great propulsion or expansiveness as required, he brought out every glory in Puccini’s opulent score, and he even resurrected from the manuscript a short scene in Act I involving Indian Billy Jackrabbit.”

—Bill Zakariasen, Daily News

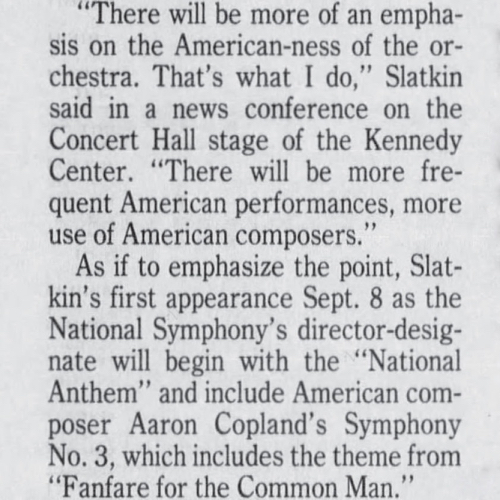

Slatkin was selected to succeed Mstislav Rostropovich as the orchestra’s fifth music director with a tenure to begin in September 1996.

“A few months earlier, I had conducted a concert with the orchestra as a kind of tryout for everyone. At intermission, a visitor came to the dressing room and told me that he hoped I would come to Washington. That gentleman was Bill Clinton.”

—Leonard Slatkin

Slatkin led the Philharmonia Orchestra in works by Schuman, Barber, Bernstein, Ives, and Gershwin, among others, at the Royal Festival Hall.

“Conductor Leonard Slatkin is a tight ball of energy on the podium: I don’t recall anybody jumping so much, right off the ground. Yet his effect is very precise and demanding.”

—Tom Sutcliffe, The Guardian

Daniel was born at 5:30 p.m. at Barnes Hospital in St. Louis and weighed 8 pounds, 5 ½ ounces. He is now a composer for film and television.

“The confluence of events of turning 50, having a new orchestra and a first child all at once is exhausting. Most important to me is having a child in the family,” Leonard Slatkin stated in an August 1996 interview with the St. Louis Jewish Light.

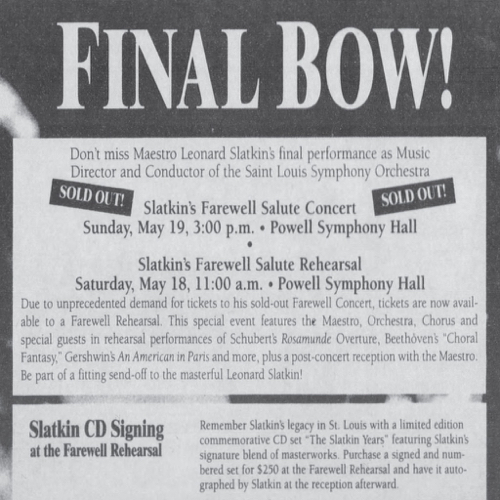

Slatkin’s final weekend included sold-out subscription concerts with guest artist Yo-Yo Ma, followed by a farewell concert and gala.

“Sunday’s gala was not only a tribute to Slatkin, but a final chance for the conductor to make music the way he does best. The soloists included artists with whom he has enjoyed long association, and the repertoire included signature works such as Gershwin’s An American in Paris and a final world premiere of a work jointly written by Slatkin and five composers whom he has championed.”

—Philip Kennicott, St. Louis Post-Dispatch

The program comprised works by American composers—Leonard Bernstein’s Candide Overture, the world premiere of Claude Baker’s Into the Sun with narration by Senator Edward Kennedy, Howard Hanson’s Symphony No. 2, Dominick Argento’s Casa Guidi with mezzo-soprano soloist Frederica von Stade, and Harlem by Duke Ellington.

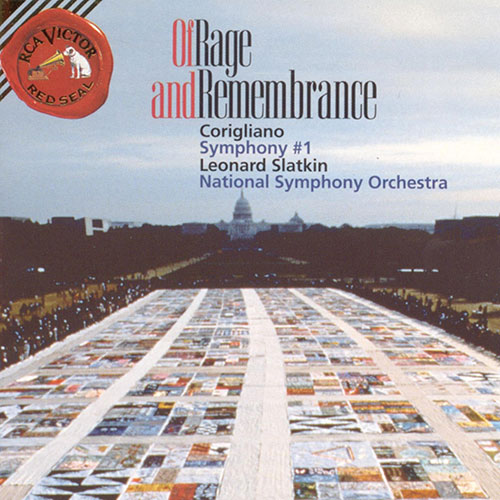

Slatkin’s first recording with the NSO was named Best Classical Album of 1996 at the 39th Annual GRAMMY Awards. John Corigliano’s First Symphony, “Of Rage and Remembrance,” was inspired by the Names Project AIDS Memorial Quilt and by the feelings of loss and anger the composer felt after losing friends and colleagues to the disease.

Slatkin held a three-year appointment with the orchestra. He also completed a number of recordings with the ensemble, notably Haydn’s London Symphonies and a Vaughan Williams symphony cycle.

“Leonard Slatkin is probably the leading ‘American’ stylist [of English music]. Slatkin has put in a lot of time and effort to make himself a fine conductor of British music, so much so that he is well-respected and liked by British audiences and performers.”

—Roger Hecht, American Record Guide

Following a state dinner for Chinese President Jiang Zemin, Slatkin and the National Symphony Orchestra performed a 30-minute program of works by Bernstein, Anderson, Gershwin, and Copland on the South Lawn. The finale was Sousa’s “The Stars and Stripes Forever.”

“Sometime I also would like to play some flute,” Jiang said to President Clinton at the concert’s conclusion. “I know you play very good sax.”

In cooperation with the National Symphony Orchestra and the American Symphony Orchestra League, Slatkin started the National Conducting Institute, designed to help conductors make the transition from leading student or part-time orchestras to full-time, professional ensembles.

“It is one thing for a young conductor to have an opportunity at universities and conservatories to tell other students what to do, but it is quite another matter to direct pros,” Slatkin explained. “We developed a three-week program in which four or five conductors experience the challenge of being confronted by a world-class orchestra.”

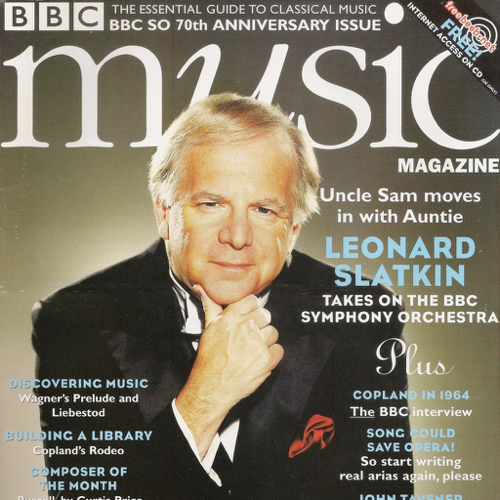

Slatkin had worked with the BBCSO several times prior to the appointment, touring with them and leading mostly contemporary music. He held the post of chief conductor for four seasons, which included notable performances at the Proms.

The American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers recognized Slatkin for his career-long commitment to American composers and new music. The awards ceremony took place at Lincoln Center’s Walter Reade Theatre in New York City.

“What we are doing is in the spirit of this tragic time. Unity through music is now the message, and we can use our sounds to help underscore the long healing process that must take place. I am honored to be doing the Last Night. Maybe more than ever.”

—Leonard Slatkin in The Guardian, September 13, 2001

“Just a few days after 9/11, this was the most difficult concert I ever led,” Slatkin reflected. “Changing the traditions of this festive evening caused much controversy. There is a video of the Barber Adagio that says it all.”

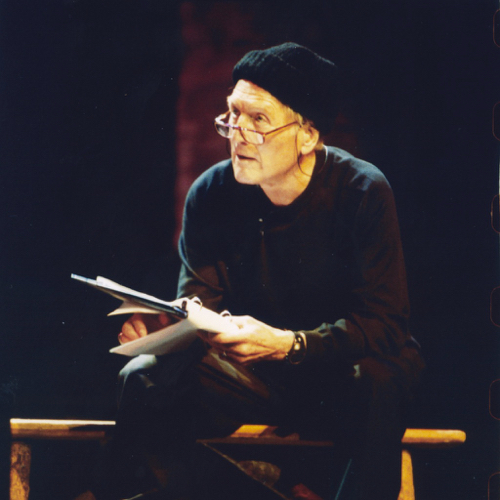

This charity event for Paul Newman’s “Hole in the Wall” camps took place in Avery Fisher Hall at Lincoln Center. Participating celebrities included Julia Roberts, Gwyneth Paltrow, Matt Damon, Morgan Freeman, Meryl Streep, Kevin Kline, Danny Aiello, Alec Baldwin, Philip Seymour Hoffman, James Naughton, Brian Dennehy, and Joanne Woodward. They performed a concert version of playwright A. E. Hotchner’s adaptation of short stories by Ernest Hemingway with incidental music by Copland.

The American Classical Music Walk of Fame in Washington Park combines classical music, mobile technology, public spaces, and a dancing fountain. By downloading a mobile app, visitors can hear musical samples and read more about the featured classical musicians while discovering the pavement stones engraved with names of Hall of Fame inductees throughout the park.

“To watch Leonard Slatkin in action is to really watch Leonard Slatkin in action. When he conducts the National Symphony Orchestra, he lunges, dips, jumps, and pivots. The audience begins to understand why the podium has a guardrail. Slatkin brings the same energy to educating his audience and encouraging young musicians. When the DC Youth Orchestra was in trouble, Slatkin pulled together a group of angels to support the group. … He founded the National Conducting Institute to give young conductors the chance to work with a major symphony. Nurturing talent is only part of his mission. He is committed to nurturing audiences.”

—Leslie Milk and Ellen Ryan, Washingtonian

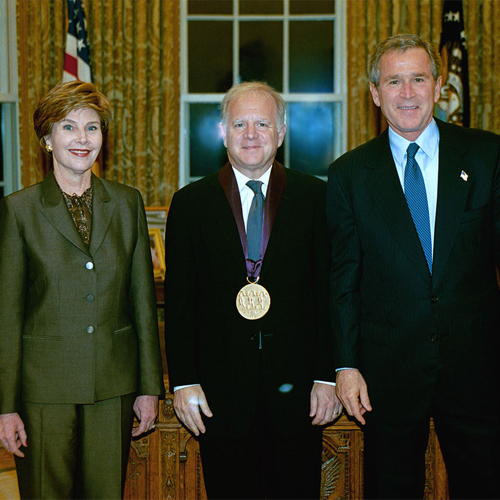

Leonard Slatkin was presented with the highest award given to artists by the U.S. Government in an Oval Office Ceremony with President George W. Bush and First Lady Laura Bush, Honorary Chair of the President’s Committee on the Arts and Humanities.

“The arts are an invaluable source of this country’s vast creative output. To be recognized for any part of that spirit is indeed a humbling honor.”

—Leonard Slatkin in The Washington Post

“We already call him the maestro. Now we may call him chevalier,” the Washington Times reported on October 20, 2004.

At the ceremony held at the French embassy, Jean-David Levitte, France’s ambassador to the U.S., praised Slatkin for his “immense contribution to French-American friendship” through activities such as the Kennedy Center’s Festival of France earlier that year.

“My own conducting teacher, Jean Morel, was French and, to a large degree, I owe much of this honor to him,” Slatkin said.

The Gold Baton is presented annually for distinguished service to American orchestras. The League’s highest honor, the award recognizes those who champion and advance the cause of symphonic music throughout the nation. The 2005 award celebrated the contributions of “Leonard Slatkin, whose imaginative musical leadership has served America’s orchestras, composers and young conductors with unparalleled vision and passion.”

Bolcom’s two-hour song cycle was recorded in Ann Arbor with Slatkin conducting the University of Michigan School of Music Symphony Orchestra and a massed U of M choir. Slatkin’s wins were in the categories of Best Classical Album and Best Choral Performance.

Slatkin told the Detroit Free Press: “It’s hard to imagine once you’ve heard this piece not to be influenced by it. That for me is the definition of a masterpiece. It’s not just the scale of the work: Very few pages go by where Bill’s voice isn’t heard, and that is the sign of a great composer. By the end of the work we feel Bill’s taken us on this incredible journey.”

Slatkin became a front-runner for the position after conducting performances in May 2007 with Walton, John Williams, and Prokofiev on the program. He was asked to return to conduct summer concerts at Meadowbrook, one featuring the music of Beethoven and the other starring the Von Trapp Family Singers.

“It was something I hadn’t experienced in a very long time,” Slatkin said in a press conference in Orchestra Hall. “This is not just an orchestra, this is a family. There was no question this was not just the place I wanted to be, but where I should be.”

Slatkin recorded the album in Nashville, where he served as the Nashville Symphony’s music adviser from 2006 to 2009.

“Magnificent works deserve an equally stellar performance. Leonard Slatkin’s leadership of the Nashville Orchestra rises to that expectation. The ensemble delivers a thoughtful and insightful performance of Tower’s works. … Absolutely a worthwhile representation of the best that American art music has to offer.”

—Mike D. Brownell, AllMusic.com

“Slatkin’s appointment as principal guest conductor is significant. An eloquent supporter of American music, such as John Adams’ ‘Slonimsky’s Earbox’ that opened the program in brilliant fashion, Slatkin should be the perfect counterpoint to [Music Director Manfred] Honeck.”

—Andrew Druckenbrod, Pittsburgh Post-Gazette

Slatkin served in the role of principal guest conductor through the 2013-14 season.

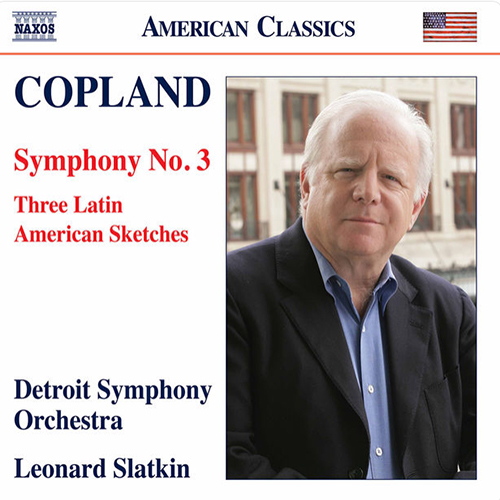

Under Slatkin’s leadership, the ONL embarked on tours to Asia and the United States and recorded the works of Ravel, Berlioz, and Saint-Saëns for the Naxos label.

“A wonderful six years of music-making and watching my cholesterol levels rise. Good thing Lyon has a lot of red wine.”

—Leonard Slatkin

Approximately 20 guests attended the wedding ceremony in the living room of their home. Federal Judge Gerald Rosen officiated, and flutists Sir James and Lady Jeanne Galway provided the music.

The couple knew each other professionally for two decades before they began dating in 2009. Leonard has long championed Cindy’s music, and their relationship grew out of mutual respect and shared experience.

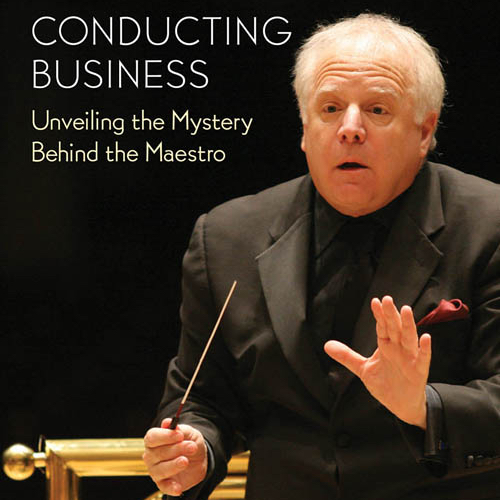

Named in honor of composer, critic, and commentator Deems Taylor, who died in 1966 after a distinguished career that included six years serving as president of ASCAP, the award recognizes outstanding print, broadcast, and new media coverage of music. Conducting Business: Unveiling the Mystery Behind the Maestro received the Special Recognition Award at a ceremony in New York City.

Performers at the event held at SubCulture in NoHo included composer David Del Tredici, saxophonist Branford Marsalis, cellist Fred Zlotkin, and pianists Joyce Yang, Joseph Kalichstein, Jeffrey Siegel, and Michel Camilo.

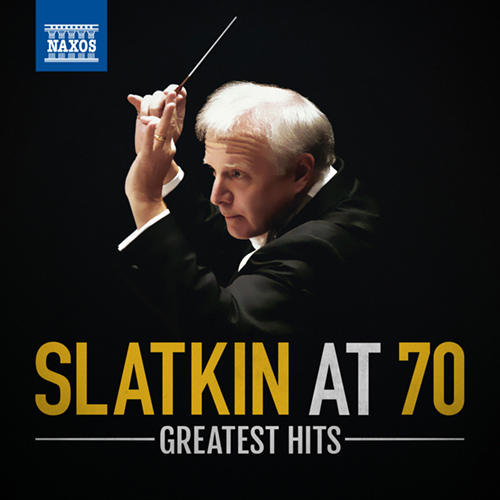

The commemorative digital album is a “greatest hits” compilation of works Slatkin recorded on the Naxos label.

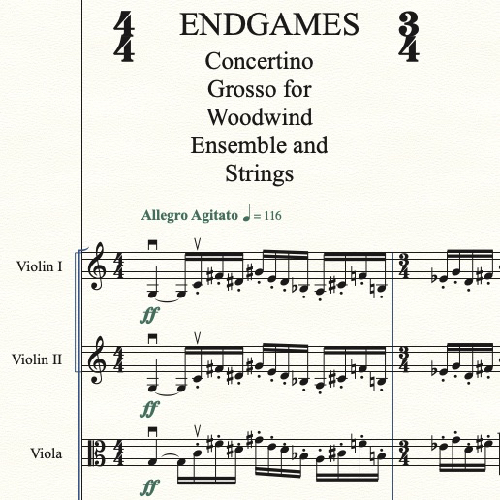

Endgames is scored for piccolo, alto flute, English horn, E-flat clarinet, bass clarinet, contrabassoon, and strings.

As Slatkin explained in his program note: “You have to feel just a little bit sorry for musicians who play instruments that fall slightly under the orchestral radar, especially those members of the orchestra sitting at the far ends of the woodwind section. They rarely have big solos, are sometimes mocked, and go unsung the majority of the time. To help remedy this situation, I have written a brief divertissement featuring six of the instruments that are often underrepresented in a solo capacity.”

“‘Kinah’ is the Hebrew word for ‘Elegy,’ and although we were not a devout family, there was always something of our Jewish heritage felt in the Slatkin household. I can only hope that this short work, about 14 minutes long, pays appropriate homage to my parents.”

—Leonard Slatkin

The opening chord comprises notes taken from the melody of the slow movement of the Brahms “Double” Concerto for Violin and Cello, which his parents were rehearsing the week of Felix’s death.

In his speech, Slatkin told the graduates: “The diploma that you will receive in a few moments should always serve as a reminder of not only your accomplishments here at NEC, but also what music means in your life. We are blessed to be able to express ourselves, as well as the ideas of others, through the miracle that takes place on the printed page. We create and bring to life virtually every emotion that exists. Treasure that and never, ever, take it for granted.”

The trip marked the DSO’s debut performances in China and its first international tour since 2001. In 20 days, Slatkin conducted 11 concerts in 10 cities across two countries.

“In each city we visited, we encountered enthusiastic audiences, some of whom have gotten to know us over the years through our audio recordings and the Live from Orchestra Hall webcast series. It was a true pleasure to play works from the American, Japanese, and Chinese cultures, and to feel the sincere appreciation of those in attendance.”

—Leonard Slatkin

Slaktin became the first to hold this honorary title with the orchestra and has enjoyed continued collaborations with the ensemble.

“The future for this orchestra is bright indeed and I’m proud to be part of it.”

—Leonard Slatkin

Subtitled “Reflections on Music, Musicians, and the Music Industry,” the book offers a glimpse into several aspects of the musical world. Slatkin presents portraits of six outstanding artists with whom he has worked, as well as anecdotes and stories both personal and professional.

He also reveals his Top 10 favorite pieces to conduct: Beethoven: Symphony No. 3, “Eroica” ~ Berlioz: Roméo et Juliette ~ Brahms: Serenade No. 1 ~ Schubert: Symphony No. 9 ~ Ravel: L’enfant et les sortilèges ~ Barber: Symphony No. 1 ~ Elgar: Symphony No. 2 ~ Shostakovich: Symphony No. 8 ~ Strauss: An Alpine Symphony ~ Rachmaninoff: Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini

Although Manfred Honeck of the Pittsburgh Symphony took home the award for Best Orchestral Performance at the 60th Annual Grammy Awards on January 28, 2018, Slatkin was honored to be nominated for the DSO recording of the work that is, in his estimation, “probably the single finest statement by an American writing in the symphonic form.”

Under Slatkin’s leadership, the DSO took on such groundbreaking initiatives as the free Live from Orchestra Hall webcasts, the annual winter music festival, and the Soundcard student ticket program. During his tenure, the DSO released acclaimed and Grammy-nominated recordings, toured Asia, played Carnegie Hall, expanded the orchestra’s educational offerings, and strengthened its connection with audiences.

As a legacy gift to the institution, he established the Cindy and Leonard Slatkin Emerging Artists Fund, which provides support for up-and-coming artists to perform with the orchestra each season.

The SLSO held a dinner onstage at Powell Hall to honor Slatkin’s legacy and celebrate his remarkable partnership with the orchestra—and the St. Louis community—over the past five decades.

Daniel Slatkin wed Bridget Laifman at the Sherwood Country Club in Thousand Oaks, California, at the base of the Santa Monica Mountains.

The happy couple lives in the Los Angeles area with their pug, Winston.