“Art is the child of nature in whom we trace the features of the mother’s face.”

—Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

She outlived our father by 32 years. I was convinced she would be around after I passed. The world never stopped for Eleanor Aller, and if it had, she would have made sure it was spinning again. Once you met her, she etched an indelible mark onto your soul. Tough, gentle, funny, and serious, Mom was a true force of nature.

Whereas I followed in the footsteps of our father, my brother Fred stepped over to the other side of the family. As soon as I started writing the chapter about Felix, I knew that he was the only person who could really tell the story of this remarkable woman.

Ladies and Gentlemen, I give you Frederick Zlotkin (he will explain that).

MY CELLO, MY MOM, AND ME

I.

“For Christ’s sake, play in tune!”

[All quotes are from Eleanor Aller Slatkin unless otherwise noted]

“For Christ’s sake, play in tune!” was one of Eleanor Aller Slatkin’s mantras. It still rings in my head, even though she has been gone for more than twenty-five years.

My mother was born into a family of musicians in New York City on May 20, 1917. Her mother, Fannie Altschuler, was a pianist, and her father, Gregory, was a cellist. He came to the United States from Russia around the turn of the twentieth century with his brothers Joe and Simeon. Their original family name was Altschuler, but they changed the name to Aller when they came to America. The story my mother told me was that they believed that there were too many Altschulers. Their father (my great-grandfather) was Jewish, but their mother (my great-grandmother) was not. She was a Tatar. For that reason, Gregory could live in Moscow rather than in the Pale of Settlement along Russia’s western border, the only area in the Russian Empire where Jews were allowed to lease land and build communities (shtetls).

***

Gregory’s first cousin, Modest Altschuler, had a significant career in Russia as both a cellist and a conductor. He studied at the Moscow Conservatory and came to America in 1893. In 1903 he formed the Russian Symphony Orchestra Society of New York City (the Little Russian Symphony), and premiered many works by Russian composers including Prokofiev, Mussorgsky, Rachmaninoff, Scriabin, and Ippolitov-Ivanov at Carnegie Hall. The orchestra disbanded just before the First World War, and Modest moved to Hollywood where he organized the Glendale Symphony Orchestra, taught, composed, and recorded film scores. He died in 1963.

In the 1970s I restored my original surname. A dear Austrian friend of mine told me that if I came from a Jewish family my last name couldn’t be “Slatkin,” and speculated that it might have originally been “Zlotkin.” When I looked at my great-grandfather’s death certificate (he was killed by an automobile in 1927), his last name was given as “Zlatkin.” The Hebrew name on his tombstone, and letters that he wrote to relatives in Russia, corroborated my friend’s assumption. The ship manifests of my grandfather and great-grandfather show “Zlotchin” and “Zlatkine.” In order to preserve the “o” sound of the original name, I transliterated the Russian to “Zlotkin.”

Eleanor had two brothers, Herbert and Victor. They were named Victor and Herbert because Gregory’s colleague in the New York theaters was Victor Herbert! My uncle Herbert, who was very close with my mother, worked for the cinematographer’s union in Los Angeles. Victor was a great pianist who made many recordings with my parents.

***

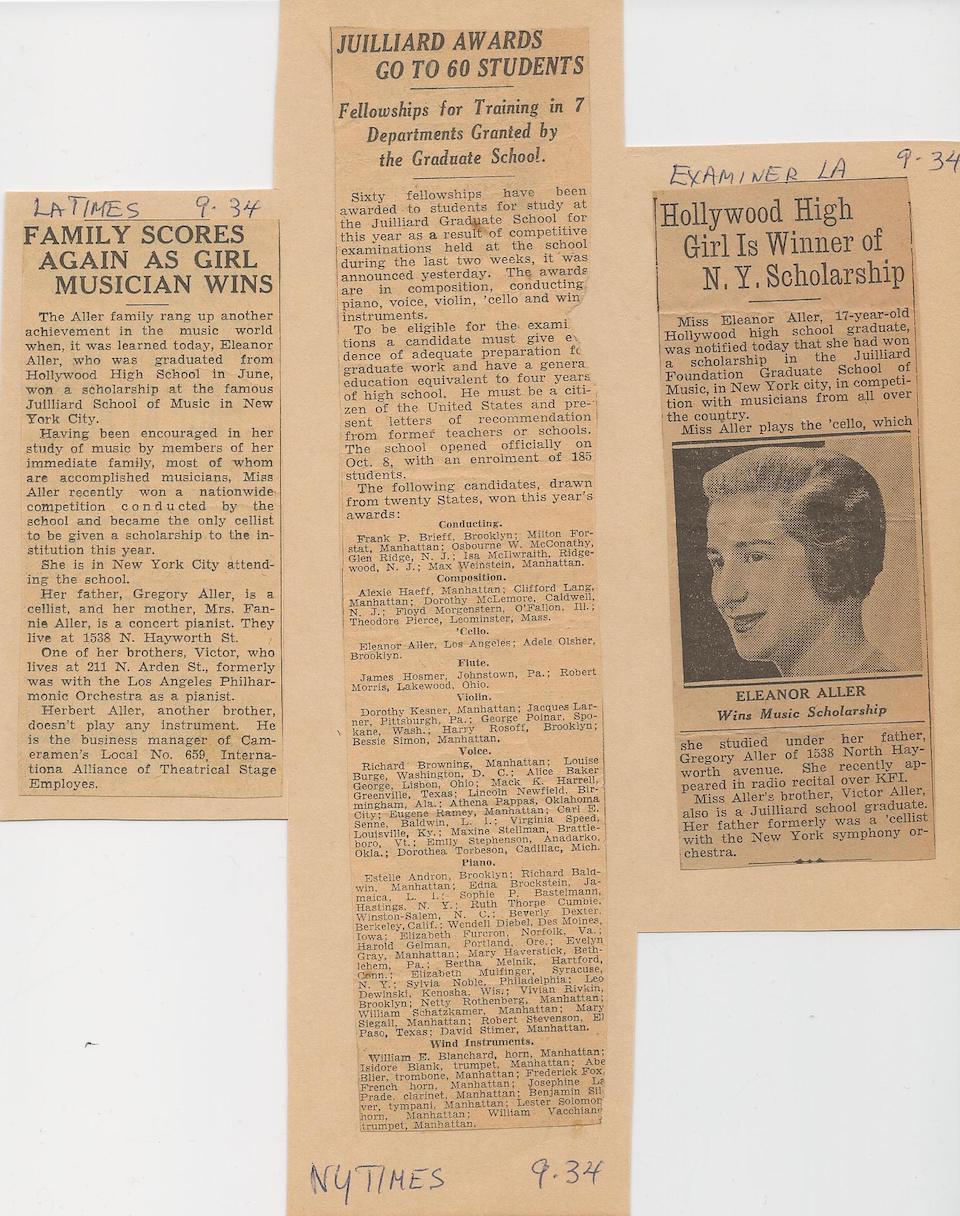

Eleanor, who began her career in Hollywood as the principal cellist of the Warner Brothers Orchestra, became one of the greatest and most-often-heard cellists of the twentieth century.

The musical life of the Aller family blossomed in New York. Gregory played in theater orchestras, and Fannie worked as a piano teacher. At five, Eleanor began studying piano with her mother, and at the age of nine she began studying cello with her father. My brother, Leonard, remembers “mother” (that’s what Len called Eleanor) playing the piano. By the age of eleven, Eleanor was playing difficult cello music. She won numerous awards and medals in competitions by the age of twelve, and she performed with her brother Victor at Carnegie Hall.

If my mother’s mantra was, “For Christ’s sake, play in tune,” her father’s mantra was, “We don’t talk about these things.” This was a common mantra for Jewish people who immigrated to the United States in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Life was so very difficult, and there seemed to be a tacit agreement never to burden future generations with the horrors and humiliation that their families endured for centuries.

Gregory was extremely strict with his students and his old-world teaching methods never included giving compliments. (Altschuler is, incidentally, the German word for a person of the “old synagogue.”) My mother told me about a time when she performed the first movement of the Boccherini A-Major Sonata and ran to her “pop” for his approval. All he said was, “You missed the high ‘E.’”

II.

“Too small to be a big town, and too big to be a small town.”

[Los Angeles]

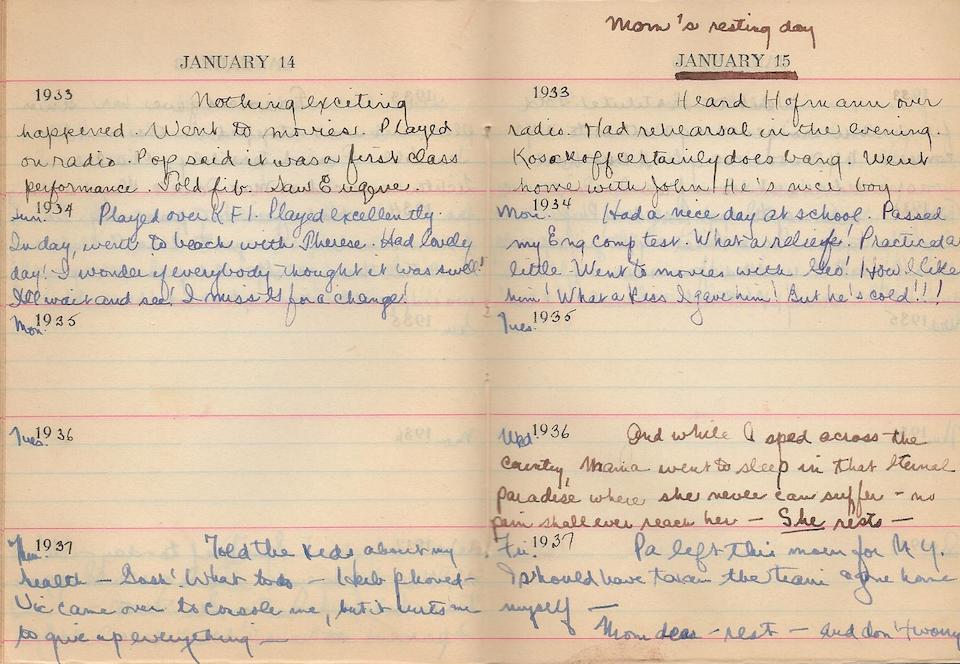

The Aller family moved to Los Angeles in July of 1931. They lived at 1538 Hayworth Avenue in Hollywood. Eleanor attended Hollywood High School and graduated in 1934. She kept a diary from the age of fifteen until the age of twenty and wrote a great deal about George Beres, a fellow student. Her feelings about George would literally swing from hot to cold from one day to the next.

***

“Music is not a competition.”

After high school Eleanor went to New York on a full scholarship to The Juilliard School of Music. Her teacher, Felix Salmond, taught most of the great American cellists of my mother’s generation, including Leonard Rose, Frank Miller, Alan Shulman, Bernard Greenhouse, and Channing Robbins. My mother studied cello and chamber music with Salmond and also studied composition with Bernard Wagenaar.

Salmond was as severe a teacher as Gregory had been. Eleanor would often see other students (most were male) crying as they left his studio. He was a dogmatic teacher who insisted that his students use the same fingerings and bowings that he did. But Eleanor, perhaps because of her experience with two older brothers and an old-world, authoritarian father, stood up for herself. Though Salmond was a great cellist, mom thought that his large hands made it difficult for him to fully master the instrument. She tried using Salmond’s fingerings but eventually confronted him, saying, “Mr. Salmond, we all have hands and fingers that are different. Mine are quite small, and I feel that I can play better if I use different fingerings.” Salmond thought about it and eventually agreed!

Among Eleanor’s possessions was a letter from her mother, Fannie, dated January 10, 1936. It was the last contact she had with her mother, because Fannie was struck by a car at Sunset Boulevard and Fairfax in Los Angeles, on January 15, 1936, and was killed. My mother most likely received the letter after her mom’s death. The car was driven by Walter Wanger, a prolific movie producer who was most likely drunk at the time. There was an inquest and a lawsuit for over $150,000, but I have not been able to obtain any record of the proceedings.

Eleanor, who was eighteen at the time, wrote to her mother in her diary as though her mother were still alive. This is her diary entry just after her mother’s death:

“And while I sped across the country, mama went to sleep in that eternal paradise where she never can suffer—no pain shall ever reach her—she rests.”

I have very few memories of mom talking about losing her mother so suddenly and tragically, so I don’t really know how it affected her. Then again, I lost my own father when I was just short of my sixteenth birthday, so I have some idea.

IV.

“My Felix is all mine forever. I never want him to leave.”

[From her diary, December 15, 1937]

Eleanor moved back to Los Angeles because of Felix. Her first encounter with Felix Slatkin wasn’t a date. It was a concert at the Hollywood Bowl on August 20, 1935, which he played as part of an award for a competition he had won. He performed Lalo’s Symphony Espagnole with the great and famous pianist-conductor, José Iturbi. The entry in her diary says, “fine fiddler.”

There is a gap of more than a year in her diary between their first and second rendezvous, perhaps due to her studies in New York. In a diary entry about playing quartets with Felix on June 3, 1937, she wrote “nice boy (?)” [sic]. When Felix suggested that they ask her to play because she was such a fantastic cellist, his colleague blurted, “A girl? Who wants to play with a girl?”

A couple of months later she had a date with Felix. Her diary entry read, “Such a sweet boy.” And then Felix put some moves on her (he asked her to read the Brahms Double Concerto with him). A week later they met up at “the Bowl” (short for the Hollywood Bowl). Felix had made a vital connection with the Hollywood studios after his Lalo performance, and he told Eleanor that he wanted to introduce her to Ray Heindorf, the contractor for Warner Brothers. A week later, Eleanor played her first recording session (“date”). She and Felix were married on December 25, 1939.

Shortly thereafter, she wrote about the studio musicians, “I never met such a lousy bunch of people.”

The Hollywood recording industry was unique. My mother often described it as a new way for musicians to earn a comfortable living playing truly inspired original compositions. It was exciting for my parents to play a major part in this new art form. By the late ’30s, the dawn of the film noir era, the film industry was gaining momentum. It literally changed Los Angeles, and the world.

In addition to other recording work, playing film scores, TV music, and record dates would sustain Eleanor and Felix comfortably for the rest of their lives. The industry had its own jargon. Most musicians referred to the industry as “the business.” Film scores were, of course, a major part of the business, but so were television scores, live television, records, and advertising jingles. The business was anything that involved a microphone and a musical instrument. Musicians referred to these sessions as “dates.” During my career I have spent many hours in recording studios, so I have firsthand knowledge of the kind of conversations musicians have on “dates.”

“Well, I started out this morning doing a film date at Fox [Twentieth Century Fox studios], then went over to CBS to play footballs [whole-notes, usually very easy and boring to play] for source music [bits and pieces of music to be inserted later, at will] for Gunsmoke [TV series] and then went over to United [one of the many recording studios] and did a record date with Ella [Fitzgerald].”

V.

“Oy, another one!”

Before I began studying cello, my music was my record player. While we were driving in the car on one of our vacation trips (either to Palm Springs or to Las Vegas) I told my parents how much I liked their recording of the Dvořák “American” String Quartet. They asked me to sing the part I liked, which I did. Mom looked at dad and said, “Oy, another one!” Now we knew that our entire family had absolute pitch.

My older brother Leonard started violin lessons with our father when I was seven. Eleanor’s cello studies with her father worked quite well, but the musical relationship between Len and Felix was not so successful. I remember a lot of yelling, and maybe even some crying. During Dad’s violin lessons with Efrem Zimbalist at the Curtis Institute of Music, he was subjected to raps of the bow across his knuckles when his teacher was particularly displeased. Since I often did what my brother did, I was ready to begin violin lessons with my father.

In addition to their work in the studios, my parents played in the Hollywood String Quartet, one of the great chamber music ensembles of its time and, as demonstrated by the longevity of their recordings, of all time. They rehearsed in our living room.

I came into the room while the quartet was taking a break and saw all the instruments propped on the chairs. I asked my parents if I could pluck the strings. First, I plucked the violin strings. To this day, I have never really cared for the thin and metallic tone of violin pizzicati, even in the best of hands and fingers. The viola was a bit better. But the cello! It had a gorgeous, big sound that rang forever. I announced, “That’s it!” and my mom said, “Great, he’ll start with ‘Pop’ next week!” (I feel fortunate that there wasn’t a double bass in the room.)

I studied the cello with Grandpa Gregory for four years. He wasn’t cruel, but he personified many of the traits of the Russian “old school,” which meant that he instilled fear. “If you don’t keep your feet in position, I will nail them to the floor.” He had a very organized pedagogical approach, which involved writing out exercises and scales and pasting them onto cardboard. He marked every fingering, string, and position into the music, and he put brackets over the stretches (extensions) in red pencil. He would always sit at the piano and play along with me, pounding out the notes to develop my intonation (the piano was constantly being tuned).

There were no compliments. After four years, I reached a point where I needed someone who could demonstrate for me. Gregory knew that at his advanced age he could no longer demonstrate adequately. I recall that once, while playing through a movement for him, he stood up and walked directly in front of me. He put his left hand on my right cheek and gave me a firm (but not painful) slap on my right cheek, with his other hand. And then he left. I was mortified, assuming that I had disappointed him severely.

My parents called me downstairs when they came home. I was scared to death. My mom said to my dad, “You take one side and I’ll take the other,” and they each planted a big kiss on my cheeks. I was totally confused. They explained to me that grandpa was so taken with my playing and my talent that he decided it was time for me to move on to another teacher!

Years later a dear older friend suggested that “old world” teaching without compliments had another purpose: it’s better for the student to get angry with the teacher than it is for them to take it out on themselves.

At the age of eleven, I began lessons with Kurt Reher, the principal cellist of the Los Angeles Philharmonic. He had been a student of Emanuel Feuermann, one of the greatest cellists of all time. Around that time, my mother summoned my dad and me to the living room, where we had a record player and a fairly good sound system. She pulled out a 78 rpm disc of Fritz Kreisler, one of the all-time great violinists, playing what I recall was his transcription of the Chopin A-Minor Mazurka. I listened for about thirty seconds and said, “Eeew, why does he do all those slides?” My mom looked at my father and said, “He’s not ready.” Another time, mom was trying to help me with something, and I sassed her, “Oh, what do you know?” She just uttered, “Accch!” and walked out of the room.

Eleanor helped me immensely in preparing for my Los Angeles debut recital, which I played at the Assistance League Playhouse on September 15, 1963. After we carefully selected, learned, and memorized the music, my brother and I had to run through the program every evening at 7:00 pm for the six weeks prior to the recital. We had to do this NO MATTER WHAT, so when the recital date arrived it wouldn’t make any difference how we felt, if we were nervous, ill, or whatever. Our hands would play the recital without us!

The recital hall was stiflingly hot that afternoon. Mom insisted that, in the proper tradition, we wear white jackets, dress shirts, cuff links, black bow ties, and patent leather shoes. “If you dress well, you will play better.” Unfortunately, my tuxedo shirt sleeves were too long for my short arms, and because of the heat, which made me and my hands sweat profusely, the metal cufflink ended up being lower than it should have been. During the first movement of the Lalo Concerto the button (screw end) of the bow caught on my right shirt cuff, and the bow went flying into the air! Because of all my preparation, I was not shaken in the slightest. I caught the bow and continued, hardly missing a beat. After the concert Kurt Reher said, “I never taught him how to do that!”

Mom made too many recordings in too many venues to enumerate, and she worked with every significant artist in every musical field, from Andy Griffith to Frank Zappa, and everything in between. She made many important recordings with Frank Sinatra, who also recorded Close to You, an entire album of Nelson Riddle arrangements, with the Hollywood String Quartet.

Her career in the motion picture industry included hundreds of films with scores by the greatest film composers of the twentieth century, including Erich Wolfgang Korngold, Max Steiner, Alex North, Jerry Goldsmith, Alfred Newman, and John Williams (John wrote a solo in Close Encounters of the Third Kind especially for her).

One of Eleanor’s most celebrated contributions as a solo cellist in films was in Irving Rapper’s 1946 film Deception. Paul Henreid, one of the stars of the film, plays the role of a cellist in a love triangle with a character played by Bette Davis and a “composer” character played by Claude Rains. The score for the film was written by Korngold. My mom said that they tried negotiating with the great cellist Gregor Piatigorsky to play the cello concerto that Korngold wrote especially for the film, but the negotiations failed, and Eleanor got the assignment. She arranged for Paul Henreid to take lessons with Grandpa Gregory for six months so that he could actually look like a cellist, while Eleanor supplied stunning performances of the last movement of the Haydn D-Major Concerto and the Korngold Concerto.

During the time of filming, Eleanor was very pregnant (with me, born about a month later!), and Bette Davis was also pregnant with her second child, Barbara. Jokes were flying around that they should change the film’s title to “Conception” or “Allegro con Embryo.” When progress on the picture seemed slow, mom urged them to hurry up, before either she or Bette exploded. My mother told me that she could feel me kick while she was recording.

My brother and I both joined the California Junior Symphony when I was around ten. It was a training orchestra led by Peter Meremblum, who had studied violin in Russia with Leopold Auer. Mr. Meremblum gave me the position of principal cellist of the “Pioneer Group,” which was for younger students. He also had me play in the cello section of the older group, so I had six hours of orchestral playing every Saturday. I soon worked my way up to being principal cello of the senior group.

At first, I shared the first stand with the principal cellist of the senior group, who was older and more experienced than I was. He was also quite a braggart, boasting during one rehearsal about his fine cello and his expensive bow. His arrogance and snobbery made me feel like a real nobody. I came home crying and told my mother about it. She advised me to say, “How wonderful that you have acquired such fine equipment.” After a year I replaced him and became principal.

VI.

“I won’t live to see the age of 50.”

[mom told me that Felix had said that to her numerous times]

Felix and Eleanor were scheduled to perform the Brahms Double Concerto with the Los Angeles Doctors Symphony early in 1963, and on February 8th of that year, I played a concert at Royce Hall on the campus of UCLA. We played the string quartet version of Mozart’s Eine kleine Nachtmusik and the Hindemith Octet. My father was unable to attend the concert because he had work to do on some arrangements for a recording session he had the next day.

After my concert, as was our family custom, we stopped by Canter’s Delicatessen and got lots of great food to take home. We heard running water in the upstairs bathroom while we were eating and assumed that dad was taking a shower. After we were finished eating, we went upstairs to our bedrooms. I heard my mother scream. Our basset hound, Jeeves, began howling. I went into my parents’ bedroom and found my mother hysterical. Felix was unconscious on the bathroom floor, and tap water was running in the sink.

Len put his hand next to dad’s nose and told us that he was not breathing. I got down on the floor and administered CPR, which I had been taught in school. This was the first and only time that I tried the procedure. I found that he expelled the air that I pumped into his lungs, which made me think that he was coming back to life. Leonard was in shock, and our mother was hysterical. She called for emergency medical help.

The medics told Len to take mom downstairs, but they let me stay with them. Perhaps their procedure was to remove those who were overwrought: if you already have one emergency, you want to avoid another. I saw them shine a small flashlight into Felix’s eyes (checking for pupil response), and I remember asking them if he was going to make it. They told me that they didn’t think so. I went limp. Then I stood up to go downstairs, but before I went, they said to me, “Don’t tell your mom or brother yet.”

Felix’s premature death from a heart attack, age forty-seven, made a deep impact on all of us. It is a scar that doesn’t heal, and it changed the lives of the three of us who survived him. Len left Los Angeles to study at Indiana University, and I was getting ready to attend Gregor Piatigorsky’s master class at the University of Southern California, so I moved into the dorm. Eleanor handled things in her own way.

After we lost Felix, Eleanor had a wonderful and slightly “wild” relationship, for several years, with a photographer named Lee Green. He was a private pilot (flying was one of Eleanor’s favorite hobbies), a skydiver, a ham radio operator, and a real bon vivant. I was fortunate to have him as a surrogate father. It helped fill the void.

Mom sold the “del Gesù” Guarnerius violin that Felix had only played for a few years. She sold our house and moved into a modest apartment. She continued working in the studios, did some private cello teaching, and coached chamber music.

I studied with Piatigorsky at the University of Southern California for a little over a year. Piatigorsky was a great artist, but he was not a great teacher for me at that time in my life. He gave master classes twice a week but did little private teaching. During his master classes my classmates and I would sit in a smoke-filled room (Piatigorsky often had three or four cigarettes going at once) and would wait to be called on. Three of the senior cellists were preparing for the Tchaikovsky International Competition, so most of the lesson time was spent on them. Piatigorsky would squeeze in my lesson either very early during the class time, when not that many had arrived, or late, when he and the class were quite fatigued.

While I was at USC, with an eye on the future, I started thinking about moving east in search of a richer classical music environment than the one in Los Angeles. Eleanor responded shrewdly. She took me to a performance of the Cleveland Orchestra conducted by George Szell. The Los Angeles Philharmonic was not one of the top American orchestras at that time, and they did not want, for fear of comparison to the Cleveland Orchestra, to let them use the Philharmonic’s hall when they came on tour to Los Angeles. So, the concert I attended was out in Glendale. I have a vivid memory of their performance of Hindemith’s Symphonic Metamorphosis. I had never heard such precision from our “local band” and assumed the difficult parts in the music were supposed to be faked.

Then Eleanor took me to a performance of the Bach Aria Group with cellist Bernard Greenhouse, her dear Juilliard colleague. Greenhouse was absolutely superb, as was everyone in the ensemble. After the concert, we went backstage, and she and Bernie embraced. Bernie looked at me and said, “So, this is the cellist?” He handed me his Stradivarius and asked me to play something. So, I did.

His eyebrows went up. Mom said to me, “Go ahead, ask him something.” I asked Mr. Greenhouse about problems I was having with my vibrato, and he explained things about vibrato that Piatigorsky had simply never analyzed. Piatigorsky was a natural, so he didn’t have to figure out how to do (or teach) these things. I was in heaven. Bernie turned to me and asked, “Would you like to learn more?” I gave him a resounding YES. And then he offered me a full scholarship to the Manhattan School of Music.

Now I had the problem of ending my studies with Mr. Piatigorsky. I first told him that I wanted to go to New York because there was so much more going on for classical music there than in Los Angeles. His response was, “One cannot get inspiration from one’s environment. Inspiration comes from within.” So, I went to my mom for advice. She suggested I tell him that I wanted to be with my brother. That seemed to assuage him, but Piatigorsky never called on me to play in the master class again.

Mom and I both knew that parents don’t usually make good teachers for their own children, but she gently suggested that, since there still were some major compositions that I hadn’t studied, we could try it. Much to my benefit, and despite what was often a contentious relationship, we were able to slip into the student and teacher roles peacefully.

Eleanor’s passion for music and musicians dominated her life, but she did have other interests. She earned a private pilot’s license and took me up in her Cessna 152, but I didn’t have the stomach for flying. She also liked sewing and made much of her clothing. She was also somewhat obsessed with the Watergate scandal.

In 1968 Eleanor accepted a position as the chair of the music faculty of DePaul University in Chicago. She was not much of a diplomat or politician, and I’m not sure that tact was in her repertoire. She told me a story about a faculty meeting at DePaul that concerned the type of training the school should offer. It was acknowledged that not all musicians can become solo, orchestral, or chamber music artists, and that some might become teachers or have to seek other ways of earning a living. After listening to her colleagues pontificate until she was about to burst at the seams, she blurted out, “I don’t know what the hell you’re all talking about. During the time that I’ve been at this school, I haven’t heard ONE student who even has a chance of getting into a major symphony orchestra!” She stayed at DePaul for two years and then returned to Los Angeles.

While at DePaul, Eleanor maintained her relationships with musicians on the west coast and cultivated relationships with other great musicians, particularly the members of the Amadeus Quartet, the Beaux Arts Trio, Isaac Stern, and especially János Starker, one of the finest cellists of his time. She frequently visited Starker at Indiana University, held master classes there, and worked privately with many of his students. Mom was cited in the 1980s as La Grande Dame du Violoncelle, a well-deserved accolade. Being around great musicians, playing, sharing ideas, and attending concerts was what gave her life meaning.

***

***

***

VII.

“Make lots of money!”

I ended up having a bi-coastal professional life and worked for several years in the Los Angeles studios. I would occasionally ask my mother for professional advice, both musically and politically. Once I told her about an attractive blonde lady on one of the studio dates who played quite poorly. I mentioned that she also seemed to have a liaison with the contractor. Mom replied, “She’s doing two jobs for the price of one.”

My mother often traveled to various cities in the United States and beyond to hear her sons play concerts. I remember one post-concert comment of hers that’s not just humorous, it’s SO Eleanor. The superb violin soloist was Elmar Oliveira, performing the Barber Concerto with my brother conducting. She was in the green room after the concert, and Elmar was not happy with his performance. He kept berating himself for playing the last movement too fast and playing the opening theme out of tune. After several minutes of this, in exasperation, mom blurted out, “Oh, for Christ’s sake, at least you didn’t kill anyone!”

VIII.

FINAL YEARS:

“You think I look good? Yeah, from the neck up.”

Eleanor had some health issues. Because of chronic hypertension, which ran in her family, she was not able to keep her private pilot’s license.

In the late 1970s she had a kidney removed, and despite years of taking medication (when I arrived at her apartment after she died, there was a virtual apothecary of prescriptions on her table), the problem became so acute that the only option, other than renal poisoning and death, was dialysis. She absolutely loathed the idea of her life being dependent on a machine.

She was hospitalized several times during her final years. Leonard and I went out to Los Angeles to consult with her unimpressive team of doctors. It appeared that the main reason they wanted to discharge her from the hospital was financial; they could get more money by admitting a new patient. I remember Len saying to me, “If we did our jobs as badly as these guys, we wouldn’t make it through the first rehearsal!”

Mom had given me “durable power of attorney,” which I think meant that if the circumstances warranted, I could have her taken off life-support. I made plans to travel to Los Angeles and be with her on October 15, 1995, but on October 12th when I returned from a concert, there was a message from one of her doctors on my answering machine: please call. This didn’t sound very good. When I called, the doctor told me that Mom had sustained a heart attack, and that they had been able to revive her; however, she then had another one, and they were not “successful” in reviving her. “So, my mother’s dead?” I asked. He started babbling. I put the phone down. This doctor had the worst “bedside manner” imaginable.

I canceled the concerts I had that weekend and immediately flew out to Los Angeles. Several of my mother’s close friends met me at the airport. I stayed at her apartment. There were, of course, a lot of tears. One of the most heart-wrenching things for me was seeing the picture of her with my son, Felix, on her lap, which greeted me at the entry. I drank most of her vodka.

She lived long enough to meet two of her grandchildren, Felix Herbert, and my nephew, Daniel Alexander. Her granddaughter, Madeleine Elizabeth, was conceived shortly after she died.

***

***

Eleanor’s Axioms

“If you don’t know it from memory, you don’t really know it.” (Somewhat ironic because the majority of her career in the studios was spent sight-reading).

“Music is an emotion” and, “if it doesn’t have heart, it doesn’t mean anything.”

She was critical of many musicians because they so often opted to “play it safe, not take a chance.”

When it came to incompetent instrumentalists she would say, “He/she can’t play ‘Come to Jesus’ in C major.”

When I told mom that brother Len had spoken highly of a violinist she didn’t like, she said, “Oh, what does he know, he’s a conductor.”

When I would over-emote, or over-phrase, especially if it was simply a statement of a theme, she would say, “If you do that, where are you going to go from there?”

“Why do they call it common sense when it’s anything but common?”

“All music critics should be required to begin their reviews with, “In my opinion …”

“I don’t care if you stand on your head, as long as it sounds good!”

***

Interview transcript from February 9, 1987:

ELEANOR:

The Hollywood Quartet, with the addition of violist Paul Robyn and cellist Kurt Reher, was making a recording of Schoenberg’s Verklärte Nacht, and the producer, Richard Jones, wanted to get program notes about the piece from the composer, who was living in Los Angeles at the time.

When asked, Professor Schoenberg said, “On the condition that they play it for me.” And so, Mr. Jones said, “Well, of course they will.”

And then he called us. We gulped four times because he was notorious to be extremely severe. But we had agreed (or Mr. Jones had agreed), and the second cellist, Kurt Reher, who had played a trio for Schoenberg, told us, “It will be hell.” But we said, “We want the program notes (or Capitol wants it). We’re going to do it.”

So that day that was chosen to go and play it for him, it was 104 degrees Fahrenheit. Needless to say, in Los Angeles, 104 in a very dry climate is hot. I don’t care where you are. And so, we all went to Professor Schoenberg’s home, walked in, and every window was shut tight—obviously no air conditioning, and one could barely breathe.

And we sat down, and I looked at my husband. I said, “We’re never going to get the program notes.” He said, “Yes we will.”

And down the steps came Professor Schoenberg (now I’ll try to describe), with a muffler, a scarf, a jacket—a wool jacket. And in front of us, the sextet, there was a table. And he sat down at the table, with the score.

He had the most piercing green eyes one could imagine. And if he ever looked up at you, he didn’t look at you: he went through you.

And so, we started. We played exactly four bars, and Schoenberg rapped on the table with the pencil. Fortunately, Kurt Reher spoke German, because his [Schoenberg’s] English was not so good. And he proceeded to say what he didn’t like about the four bars, which is the introduc …it’s really just setting. It’s not even the beginning of the piece.

And my husband very quietly said, “Professor Schoenberg, would you be kind enough to just let us play it through for you, and afterwards we’ll go back, and anything you would like we will change. And he said, “Ja, ja, ja.”

Now he had a habit of sitting and, I don’t think I can do it … of pft, pft, pft, smacking his lips. I can’t do it quite the way he did. In any case, we now played the piece through. I have to interject a thought. Because of the extreme heat, the perspiration was dripping from one’s arm onto the floor. You cannot imagine how hot it was; I can’t describe it.

When we finished, there was absolute dead silence in the room. We all thought, “Well, now we’re gonna get it. (That’s an American expression—you translate it.) And he sat there, and he looked, and he looked, and finally he said, “pft, pft,” now I’ll try to imitate: “pft, it was, pft, it was good, pft pft, it, pft, it was very good. I have nothing to say.”

Well, I think we would have all liked to have gone through the floor, because we thought we were gonna really be killed, musically. And with that he turned to his wife, whose name I can’t remember, and said, “Bring the refreshments.”

Now, you have to imagine: 104 degrees, no air, no windows open. It is sweltering. And out she comes with a tray … of bourbon and donuts. I looked at my husband, and I said, “Bourbon and donuts?” I mean, this combination … I don’t know in any language how I could explain how absurd it was.